Based on their size and weight, many marine mammals were hypothesized to have a very low, almost negligible Bohr effect.

Marine mammals Īn exception to the otherwise well-supported link between animal body size and the sensitivity of its haemoglobin to changes in pH was discovered in 1961. Though they are one of the largest animals on the planet, humpback whales have a Bohr effect magnitude similar to that of a guinea pig.

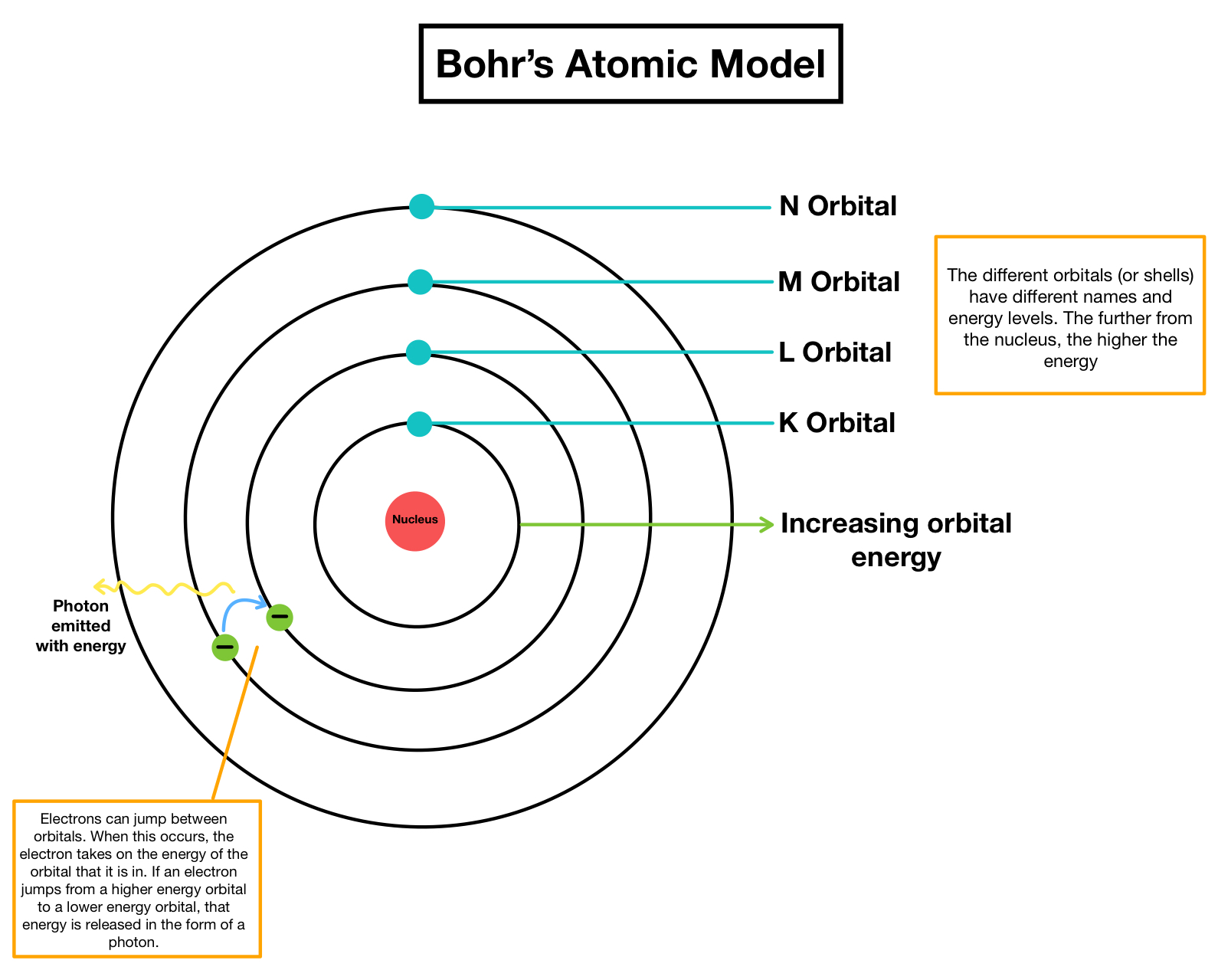

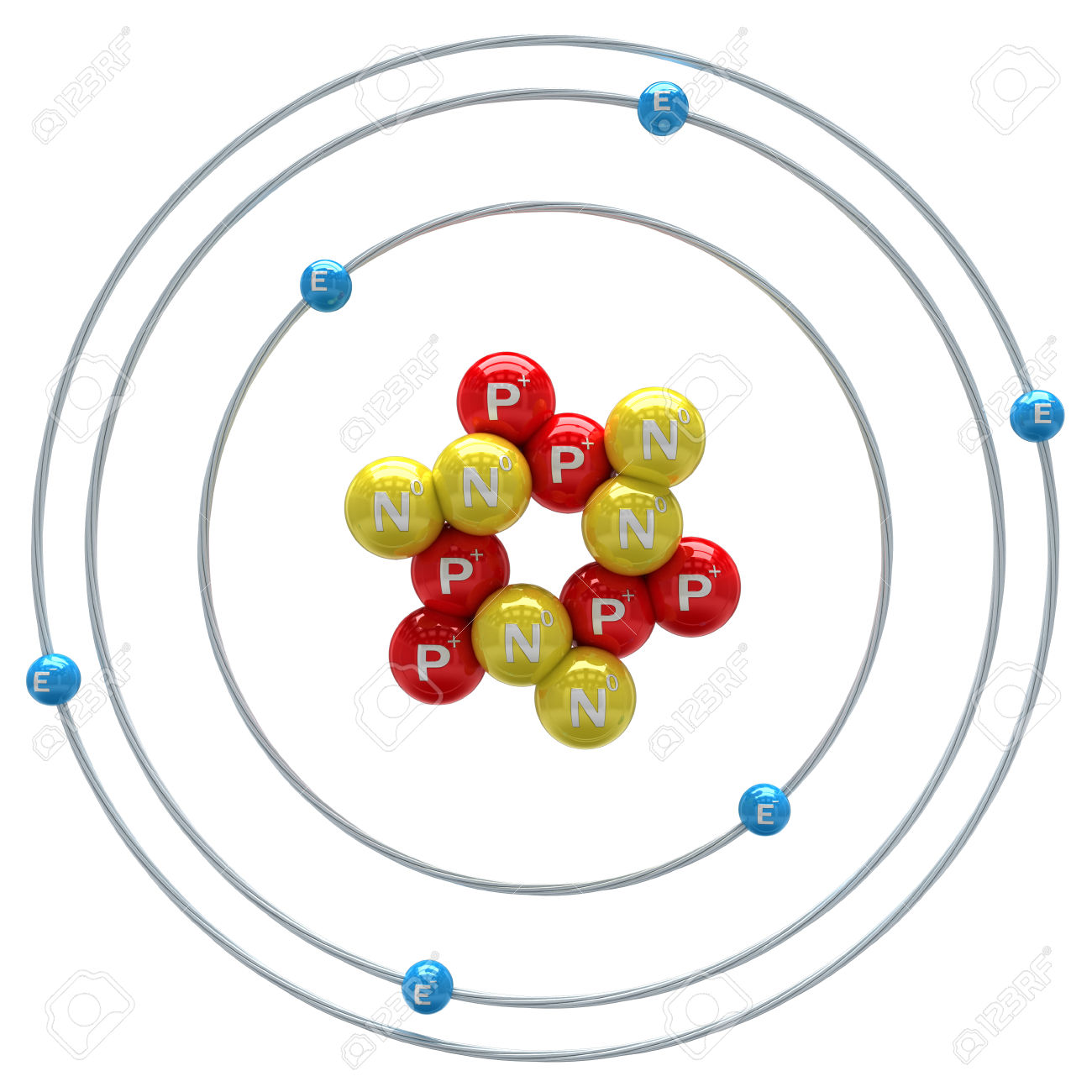

The process also creates protons, meaning that the formation of carbamates also contributes to the strengthening of ionic interactions, further stabilizing the T state. When released into the bloodstream, carbon dioxide forms bicarbonate and protons through the following reaction:ĬO 2 + H 2 O ↽ − − ⇀ H 2 CO 3 ↽ − − ⇀ H + + HCO 3 − ĬO 2 forms carbamates more frequently with the T state, which helps to stabilize this conformation. When a tissue's metabolic rate increases, so does its carbon dioxide waste production. After hemoglobin binds to oxygen in the lungs due to the high oxygen concentrations, the Bohr effect facilitates its release in the tissues, particularly those tissues in most need of oxygen. The Bohr effect increases the efficiency of oxygen transportation through the blood. Though there is some evidence to support this, retroactively changing the name of a well-known phenomenon would be extremely impractical, so it remains known as the Bohr effect.

Image of carbon bohr model full#

Though Bohr was quick to take full credit, his associate Krogh, who invented the apparatus used to measure gas concentrations in the experiments, maintained throughout his life that he himself had actually been the first to demonstrate the effect.

Īnother challenge to Bohr's discovery comes from within his lab. His proposed model was flawed, and Bohr harshly criticized it in his own publications. While this has never been proven, Verigo did in fact publish a paper on the haemoglobin-CO 2 relationship in 1892. There is some more debate over whether Bohr was actually the first to discover the relationship between CO 2 and oxygen affinity, or whether the Russian physiologist Bronislav Verigo beat him to it, allegedly discovering the effect in 1898, six years before Bohr. Further experimentation while varying the CO 2 concentration quickly provided conclusive evidence, confirming the existence of what would soon become known as the Bohr effect. Furthermore, in the process of plotting out numerous dissociation curves, it soon became apparent that high partial pressures of carbon dioxide caused the curves to shift to the right. Hüfner had suggested that the oxygen-haemoglobin binding curve was hyperbolic in shape, but after extensive experimentation, the Copenhagen group determined that the curve was in fact sigmoidal. In 1903, he began working closely with Karl Hasselbalch and August Krogh, two of his associates at the university, in an attempt to experimentally replicate the work of Gustav von Hüfner, using whole blood instead of haemoglobin solution. He had spent the last two decades studying the solubility of oxygen, carbon dioxide, and other gases in various liquids, and had conducted extensive research on haemoglobin and its affinity for oxygen. In the early 1900s, Christian Bohr was a professor at the University of Copenhagen in Denmark, already well known for his work in the field of respiratory physiology. The curves were obtained using whole dog blood, with the exception of the dashed curve, for which horse blood was used. X-axis: oxygen partial pressure in mmHg, Y-axis % oxy-hemoglobin. This is also one of the first examples of cooperative binding. The original dissociation curves from Bohr's experiments in the first description of the Bohr effect, showing a decrease in oxygen affinity as the partial pressure of carbon dioxide increases.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)